Aidan Jakfar

ترانه های عاشقانه خواهیم خواند

we shall sing songs of love

Lena Mai Merle

From the conversations conducted over the years between Aidan Jakfar and other refugees, a transcribed and edited body of texts emerged, which she compiled into a total of eight monologues and a book entitled Stimmen Afghanischer Geflüchteter aus Deutschland (Voices of Afghan Refugees from Germany).

It is an examination of the Federal Republic of Germany under the aspect of immigration. Based on this body of texts, Jakfar interweaves various cinematographic means in we shall sing songs of love to manifest different speaker positions, voices and their realities. Where do we speak from, where do we sing from and to whom?

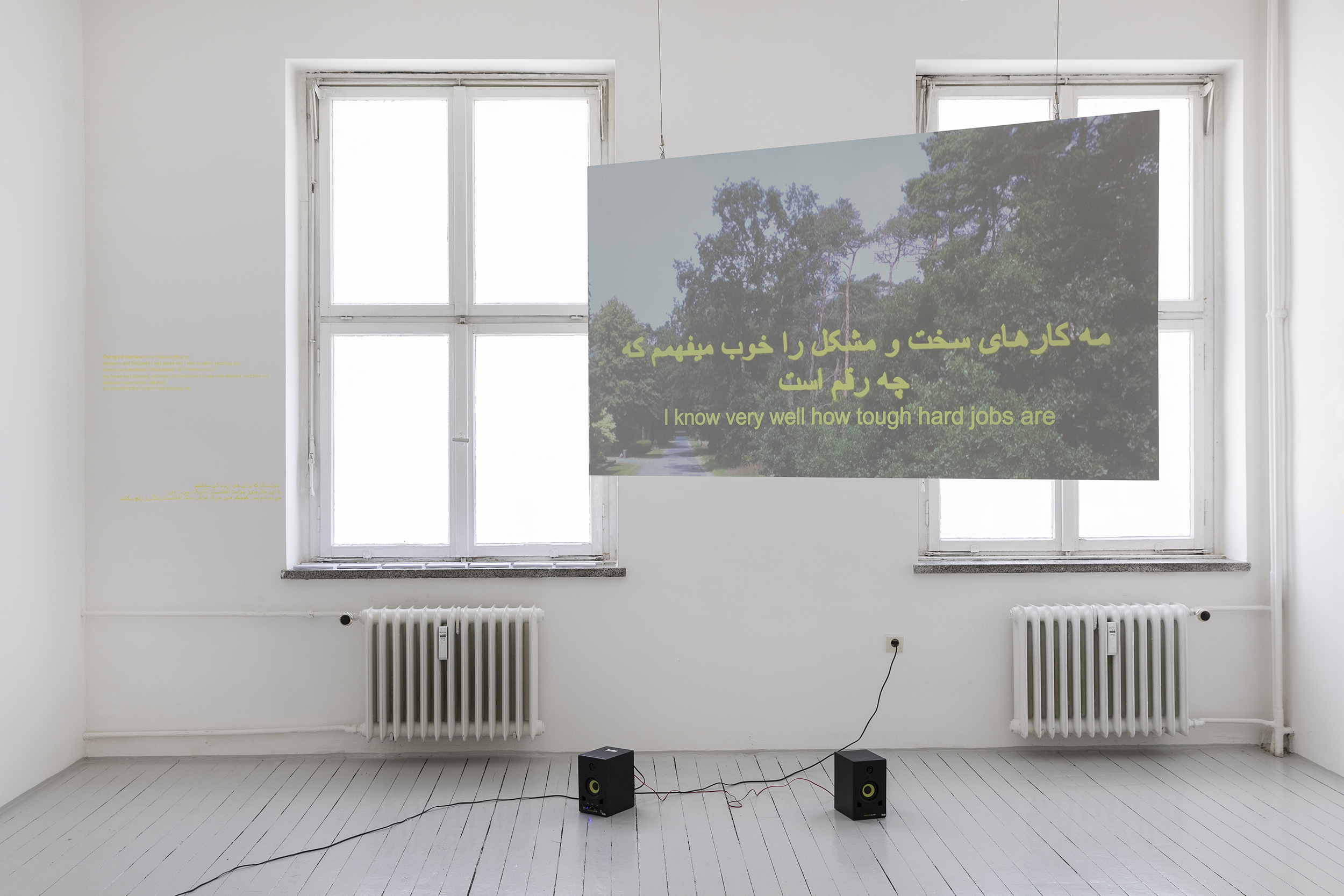

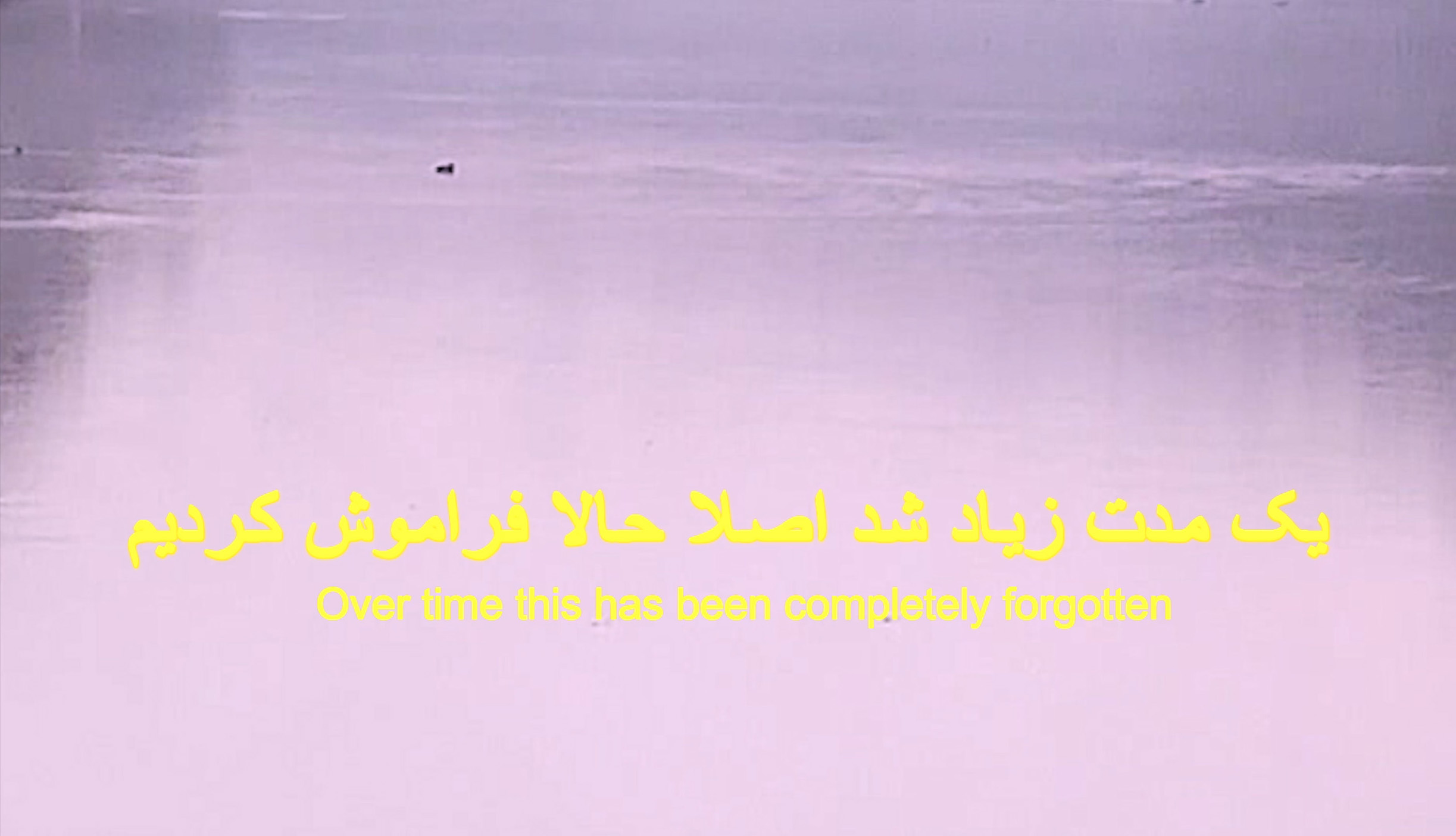

One of the voices from the monologues speaks in the film Hollage der Ort an dem wir jetzt leben (Hollage the place where we live now, 2021). It belongs to a woman with a Marxist background who fled to Germany with her family in the late 1990s. Set in a rural area, the still camera shows one (almost kitschy, reminiscent of the cinematic sentimentality of Persian cinema) landscape shot after another. Hollage, a place that immediately disappears from your mind due to the abundance of poetic images of nature and scintillating play of light. Aesthetically, the pictures are reminiscent of old mobile phone photos. Simultaneously, the same distance prevails between the viewer and the unyielding European nature as in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. However, there is not a single person to be found, not a single wanderer rising above the sea of fog (Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer). The impression is that one is in a non-space, perhaps a shimmering fantasy or a better „thereafter".

In the foreground of each shot are larger subtitles in Farsi (Farsi-speaking audience) and smaller ones in English (international audience). This audiovisual transition into two concise, parallel lines frames each individual image so that it could stand by its own as a quotation image, like a movie postcard. From the perspective of the translator, the mediator of interpretation between language(s), there are two ways to subtitle a film:

"Domestication and foreignization are strategies in translation that refer to the extent to which translators adapt a text to the target culture. Domestication is the strategy of adapting a text closely to the culture of the language into which it is translated, which may mean the loss of information from the source text. Foreignization is the strategy of retaining information from the source text and involves deliberately breaking with the conventions of the target language in order to preserve the meaning of the text.

In his 1998 book The Scandals of Translation: Towards an Ethics of Difference, Venuti states that 'domestication and alienation have to do with the extent to which a translation adapts a foreign text to the translating language and culture, and the extent to which it rather signals the differences of that text'. "*

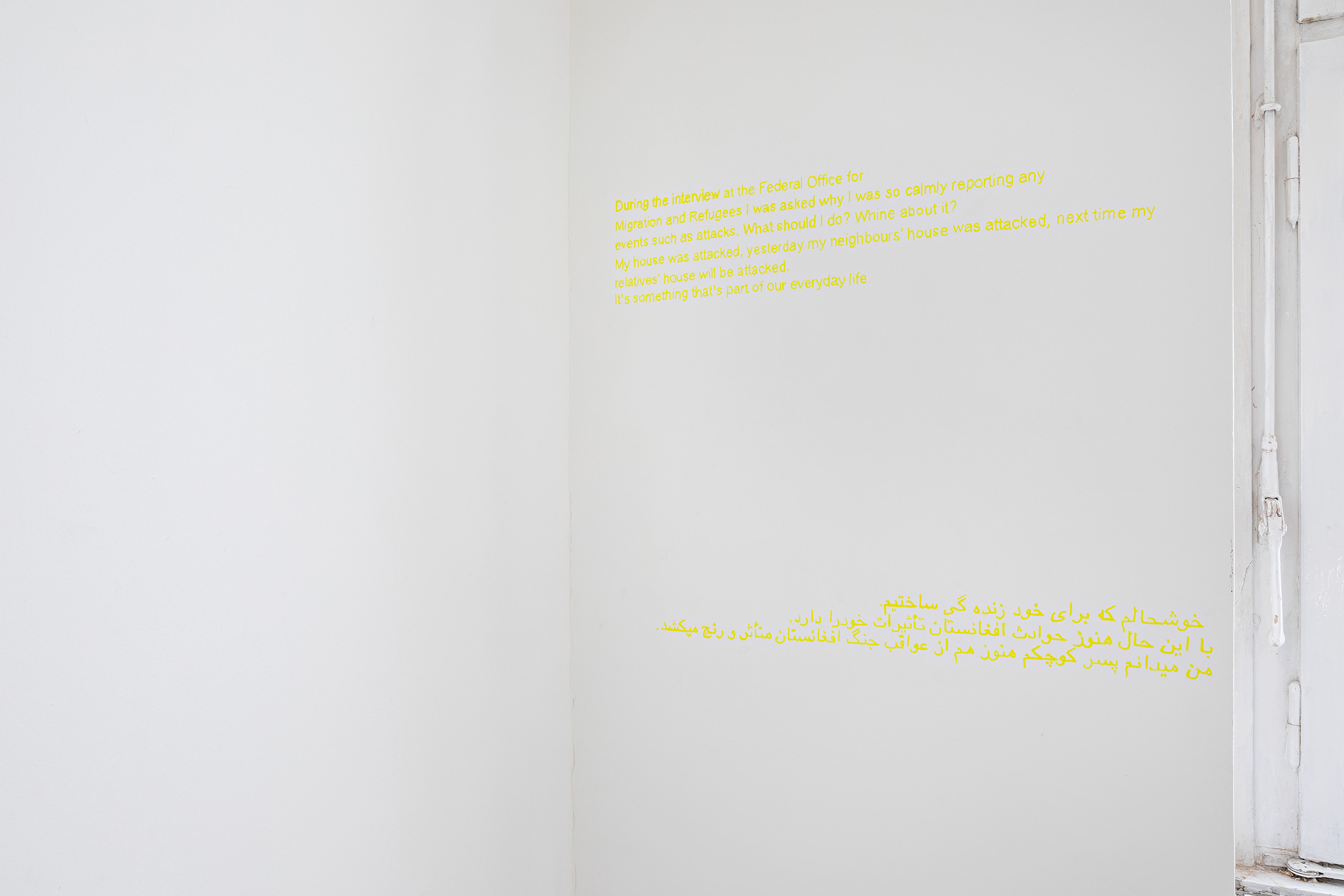

The position of speech and the related performance of trans-lation (crossing over) are thus already present in the subtitling. This form is used in Aidan Jakfar's wall work as a means of effecting a displacement, so that a new, separate place of speaking-from is created within the subtitles on the wall, which already intrinsically includes a displacement. By transposing the subtitle form and thus the cinematic image space (and non-space) to the white exhibition wall, one is exposed to the incomprehensibility of the related events. You are in the film. In addition, "the politics that often seem so abstract are objectified and expressed through the realities of the people "** who are quoted here.

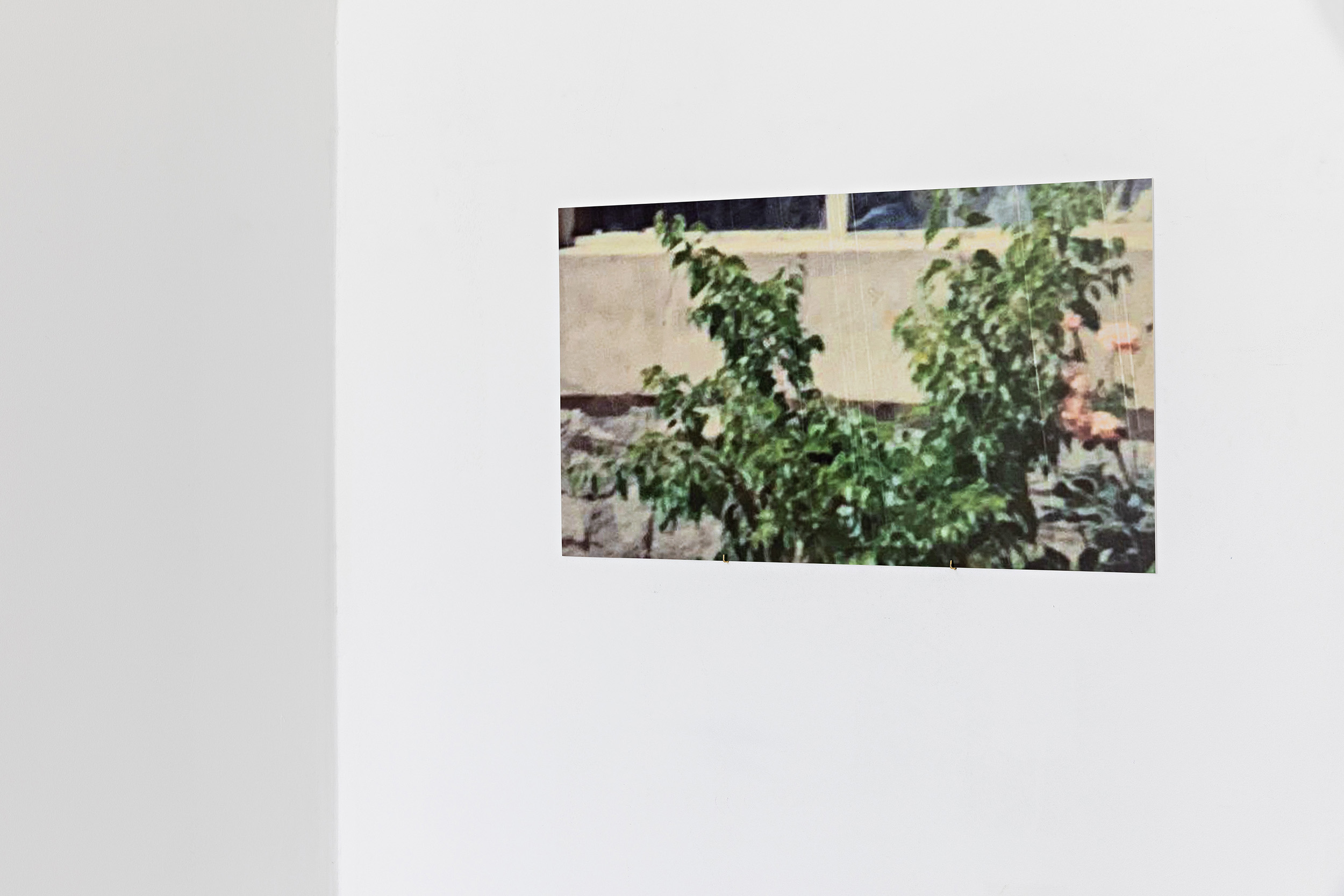

We encounter a speech written by the same speaker from the film in connection with an old photo from Afghanistan. We don't know exactly when it was taken, but it must have been in the 70s.

There are clear signs of use, the photo is faded in places, and the decision not to retouch the image with digital tools by using surgical mouse work appears in the worn colour fields, illustrating an incorporating use of memory aids/mnemonic devices.

A happy woman holds up a baby in front of a rose bush; below, another child's mop of hair peeks just over the edge of the picture. The picture is cut in such a way that the faces, especially those of the children, are no longer visible. One might recognize the woman, but one would have to imagine the other faces. Once again, the cinematic format of 16:9 appears and the ornamental bush and the baby once more refer to the romantic Persian television of the 70s.

The speech calls on us to carry on despite the intimidating conditions, in which we might feel powerless. Above all, it points to the common interests of workers and migrants: "We must set goals that will save us from oppression", "We must move forward in unity and solidarity with others, regardless of our differences", "We have to move together with others, think about the change of our lives".

Read together with the exhibition title "we shall sing songs of love", the whole thing transcends the chorus, which in theatre represents the public by collectively singing a song (whether polyphonic or not). It is a call to action and to discourse in the political sphere, to Arendt's Vita Activa through the plurality of songs in the responsibility of the individual to the whole without the luxurious pleasure of the tragic figure.

* Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domestication_and_foreignization

** Quote Aidan Jakfar from "Stimmen Afghanischer Geflüchteter aus Deutschland" adapted for readability.

Admiralitätstraße 71, 20459 Hamburg